Before perfumery became an industry, it was, in essence, a study in slow transformation—a meticulous, almost sacred dialogue between humans and flowers. Techniques like maceration and cold enfleurage survive as artifacts of this era, where scent was not extracted but gently invited. These methods are rooted in the belief that true aroma cannot be seized; it must be convinced to part with grace. In this way, they capture the fragrances of nature’s most delicate voices—blossoms too frail for heat or pressure.

At the intersection of patience and physics, these time-honored techniques rely on molecular temptation, presenting warm fat as a hospitable refuge for volatile oils. Rather than forcing scent through intensity, the process draws it out slowly, preserving its nuances. The result is not just an extraction but a resurrection: a scent that holds memory, texture, and soul. Unlike high-intensity engineered formulas, this is fragrance as quiet recollection.

What emerges from these methods is a substance rich in layers and astonishing in truthfulness. These absolutes carry the density of time, the labor of seasons, and the intimacy of touch. They are not fast imitations but faithful portraits—evidence of what happens when craftsmanship and nature are given time to trust each other.

The Warm Embrace: Unlocking Scent with Maceration

Maceration can be envisioned as a gentle, warm immersion, a process of sensory osmosis. Here, botanicals are submerged in a vessel of purified, odorless fat or oil that is heated just enough to liquefy and become more receptive. This slight increase in temperature is not for aggression, but for encouragement; it energizes the aromatic molecules, making them more eager to migrate from their cellular confines. The entire system is then left undisturbed, allowing the silent transfer of scent to unfold.

The driving force is a phenomenon of molecular magnetism. The lipophilic (“fat-loving”) nature of the aromatic oils creates a powerful attraction to the surrounding fatty solvent. This chemical affinity initiates a natural drift, as scent molecules detach from the plant matrix and eagerly dissolve into the more hospitable fat. It’s a quiet exodus, a journey from a crowded space to an open one, governed by the universe’s preference for equilibrium.

This method is a testament to the elegance of selective chemistry. The fat is a discerning host, inviting only the oil-based aromatic compounds to the party while leaving the unwanted, water-soluble elements behind. The result is a fragrant infusion, a pommade, where the fat has become a rich library of the botanical’s essence, holding its complete story in a stable, preserved form.

The Silent Courtship: Cold Enfleurage

For blossoms of almost spectral fragility, such as jasmine and tuberose, even the mild warmth of maceration is too great a shock. For them, perfumery reserves its most reverent and painstaking technique: cold enfleurage. This method is a completely heatless courtship, relying on the astonishing fact that these flowers continue to exhale their scent for hours after being picked. Enfleurage captures this final, beautiful breath.

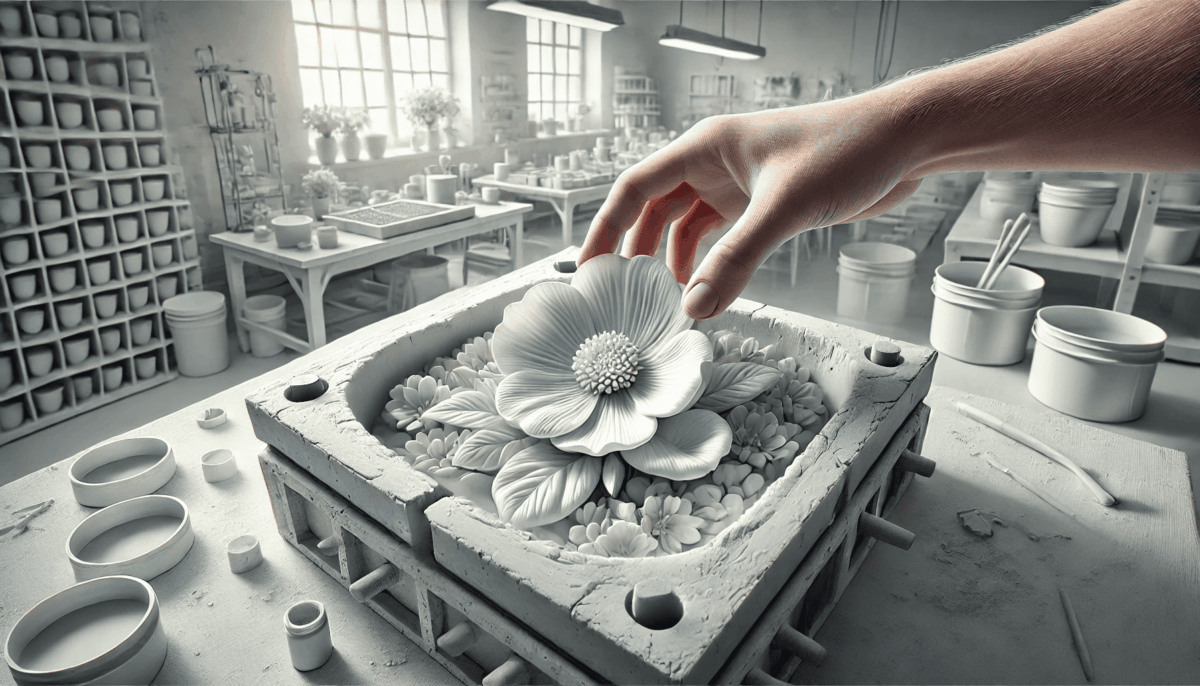

The apparatus for this art form is the châssis, a wooden frame holding a pane of glass coated in a pristine, odorless layer of fat. Freshly plucked blossoms are laid upon this fatty bed by hand, and the frames are stacked to create a sealed chamber of olfactive exchange. Here, in the quiet dark, the fat passively absorbs the fragrant molecules the flowers release as they fade, becoming a time-lapse photograph of their life cycle.

This is a ritual of daily devotion, repeated for weeks or months until the fat can absorb no more. The cycle is a masterpiece of gentle persistence, demanding an artist’s touch at every stage.

- Preparing the Canvas: The fat’s surface is scored with fine grooves, multiplying the area available to trap the fleeting scent molecules.

- The Floral Offering: Each blossom is individually placed onto the fat, a mosaic of fragrant potential laid upon a silent, waiting trap.

- A Daily Renewal: The following day, the exhausted flowers are delicately lifted away and a new, vibrant generation takes their place, continuing the slow saturation.

The Great Liberation: Isolating the Absolute

Once the pommade is saturated to its chemical limit, it holds the complete fragrance, but in a solid, unusable form. The final act of this drama is the liberation, a process of washing the pommade with a high-proof spirit, typically pure alcohol. This step introduces a new, even more alluring solvent into the system, initiating a second, decisive molecular migration.

The chemistry here is a story of competing affections. While the aromatic oils are comfortable in the fat, they are exponentially more soluble in alcohol. When introduced, the alcohol acts as a powerful rescuer, pulling the scent molecules out of the fatty matrix and into a new liquid embrace. This clever use of differential solubility allows the perfumer to cleanly separate the treasure from the vessel that captured it.

After a period of vigorous stirring, the fragrant alcohol is decanted, leaving the now scentless fat behind. The final purification involves gently evaporating the alcohol under a mild vacuum, a process that ensures the delicate scent molecules are not damaged. What remains is the absolute—a viscous, intensely aromatic essence that is the most faithful and complex portrait of the living flower imaginable.

Echoes in a Modern World: The Legacy of Patience

In today’s fast-paced industry, maceration and enfleurage are the slow-food movement of perfumery—rare, revered, and economically challenging. The cost in human hours and raw botanical material is staggering, making them unfeasible for nearly all but the most dedicated artisanal producers. These methods have been almost entirely superseded by solvent and CO2 extractions, which are infinitely more efficient and scalable.

Yet, despite their commercial obsolescence, they remain the gold standard of naturalism. The absolutes they produce possess a certain “life” and a three-dimensional complexity that is the benchmark against which all other extraction methods are measured. They are a library of scent, containing the heavy, heady, and waxy molecules that are often lost or altered in processes involving heat or high pressure.

The survival of these ancient arts is a testament to a philosophy that prioritizes quality over quantity. They serve as a vital connection to the historical roots of perfumery and a powerful reminder that some of nature’s most profound secrets can only be unlocked with patience. They are not merely techniques, but a tribute to the beautiful, fleeting soul of a flower.

Frequently Asked Questions

The combination of high heat and water in steam distillation is a violent environment for the delicate organic compounds that create a flower’s nuanced scent. For flowers like jasmine, the heat chemically alters or completely destroys key molecules (like indole), effectively “boiling away” the rich, deep, and lifelike characteristics. The resulting oil is a thin, sharp caricature of the living blossom.

The ideal fat for enfleurage must be completely odorless to avoid contaminating the final product, and it must have a specific physical consistency at room temperature—soft enough to allow molecules to be absorbed, but firm enough to not melt. Historically, a purified mix of animal fats (pork and beef) was perfect. Modern artisans often use proprietary blends of hydrogenated, odorless vegetable butters.

The key difference lies in the types of molecules each contains. Distillation, which produces essential oils, primarily captures small, light molecules that can travel with steam. Solvent-based extractions, which produce absolutes, capture a much wider range of molecules, including the larger, heavier, and waxier ones. This makes absolutes more viscous and gives them a richer, deeper, and more complete scent profile that is truer to the source plant.